Ethics and the Carbon Budget

5 September 2019 | BY Jeremy Moss, UNSW | Ethics and Exports

If dangerous climate change is to be avoided, there is only a limited amount of GHG emissions that the world can emit. According to the IPCC, if we are to limit the rise in global temperatures to less than 2°C above pre-industrial levels, or the more ambitious 1.5°C goal, total global anthropogenic carbon emissions since industrialisation must be drastically reduced.

According to the IPCC special report on climate change, to reach a 66% chance of limiting temperature rise to 1.5°C, the remaining carbon budget (the total amount of emissions we can admit and have a chance of avoiding dangerous climate change) must be limited to around 420 GtCO2 (IPCC, 2018, p.96). This budget is being depleted at a rate of 42 ± 3 GtCO2 per year.

Conceptualising the carbon emissions reduction necessary in terms of the familiar concept of a ‘budget’ offers a clear way to identify emission reduction goals and track progress toward their achievement, both globally and at the domestic level.

Importantly, the upper limit of the carbon budget will depend on how the parameters are set; the more ambitious the goal, the smaller and more restrictive the budget. For example, the IPCC recently released a report noting the benefits of keeping temperature rise to 1.5C (IPCC, 2018), a limit which, if imposed, would seriously squeeze the budget.

How we set the carbon budget also pivots on shifting environmental realities. Perhaps most crucially, if the ‘sinks’ that absorb emissions (land and ocean) deteriorate and become less able to do so, or the permafrost melts and releases additional GHGs, the budget becomes more restricted still.

Even though the budget has a specific temperature and emission target, there is no sharp boundary between amounts of emissions that are harmful. Increasing concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere are progressively more dangerous and expose human society to greater harms by each increment. Alarmingly, we have already seen temperature increases of around 1C.

Changing the parameters of the carbon budget alerts us to the role that ethics plays in the determination of the carbon budget and hence our emission reduction tasks. The carbon budget is not simply a scientific target, but one that is saturated with ethical judgements.

For example, consider that the 2C target discussed by the IPCC is said to have a ‘reasonable chance’ of avoiding dangerous climate change, which means around a 66% probability. If we were to give ourselves a better chance (e.g. 90% as opposed to 60%), the budget must be reduced, again restricting future allowable emissions. So, how likely, demanding and costly mitigating climate change will be depends on the risks we are prepared to take.

Ethics also plays a role in setting the temperature goal. Adjusting the target from 2C to 1.5C degrees is, in part, a decision based on ethical reasons. As the recent IPCC report makes clear, there will be less severe harms to human societies and the environment with a 1.5C target. Why is this an ethical issue?

The fundamental reason we want to avoid, or at least limit, climate change does not simply concern the nature of the changes the climate will undergo, but comes down to the harmful impact of those changes on human society and the environment. Deliberating about what kinds of harms we are prepared to accept involves making value judgements about the interests of others and how much they should or should not have to suffer. Asking whether, say, risking some of these harms is worse than the cost of avoiding them is fundamentally an ethical question.

Justly dividing the carbon budget

Even if we were are able to, somehow, accurately calculate the ideal level of risk and harm avoidance to set a global carbon budget, this does not tell us anything about how we should divide it amongst the global community. Again, we are faced with important ethical issues.

The current method for setting individual country budgets is according to the Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDCs). As part of the COP negotiations, each country pledged to reduce its emissions by a certain amount, for example, both Australia and the U.S. have pledged to reduce their emissions by 26-28% by 2030 against 2005 levels.

However, even if all countries were to uphold such commitments, the country’s carbon budget will be exceeded. At current rates of emission, Australia is overstepping its carbon budget limit.

What, then, is Australia’s fair share of the global carbon budget? It is important to note that in Australia, more greenhouse gases are emitted per person (22.24 Mt CO2-e in 2014) than any other country in the OECD (OECD, 2016), predominantly due to reliance on coal as a source of energy.

The Climate Change Authority (CCA) – Australia’s former independent expert advisory body – considers the nation’s carbon budget for the period 2013-2050 to be 10.1 Gt of carbon dioxide equivalent (Climate Change Authority 2014, p.117). This was determined after acknowledging a range of approaches to assessing a country’s ‘fair share’ of the carbon budget as well as following considerations of equity and feasibility issues.

The CCA predicted that, if Australia continues current levels of emissions, the carbon budget will be exhausted by 2030. If, on the other hand, we are serious about limiting warming and heed the CCA’s recommendation of a 50% reduction in emissions by 2030 compared to 2000 levels (Climate Change Authority 2014, p.232), our chances are much stronger. Indeed, such an emissions reduction target is consistent with a global carbon budget that offers a “likely” chance of remaining below the critical 2°C warming ‘ceiling’.

The CAA estimation of Australia’s carbon budget raises the issue of whether countries setting their own emissions targets will result in a truly fair share of the remaining carbon budget. The U.S. and Australia, for instance, are very wealthy, boast high standards of living and are responsible for a huge bulk of the world’s historical emissions, in contrast to the proportionally smaller emissions total of developing, highly populated countries such as India.

How ought these future emission rights be divided? This is again a question that relies on ethical principles, in particular, those of distributive justice. Several principles that have been put forward to divide the budget.

According to an ‘ability to pay’ principle, emissions reductions should be set in accordance with countries’ ability to pay the associated costs (Singer 2002). On the other hand, ‘beneficiary pays’ principles say that the greater and more numerous the benefits a country has enjoyed from past emissions, the less it is entitled to emit in the future (Page 2012).

In contrast, ‘equal per capita’ principles hold that countries ought to be entitled to emit an amount of future emissions consistent with whatever is an equal per-capita share of the global carbon budget (Meyer 2000). According to historical responsibility principles, nations which have emitted highly in the past should be allocated a smaller cut of the global carbon budget than historically low-emitting countries. (Moss and Kath, 2019).

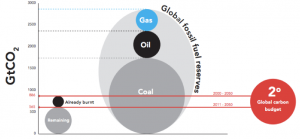

Getting the division of the carbon budget right is critical as it tells us what our emissions limits are and the overall amount of emissions that have to be divided between countries. However, it also raises important issues concerning how and if we can extract the remaining reserves of fossil fuels. According to the International Energy Agency and others, in order to avoid dangerous climate change, we can only extract and consume one third or less of the total known global reserves of fossil fuels (IEA 2012, p.3). This figure will be smaller still if the 1.5C budget is adopted.

If this is the case, it raises ethical issues about how to allocate the remaining rights to extract fossil fuels. Should traditional fossil fuel exporting nations such as Norway or Australia with already high standards of living, be allowed to continue to extract while less developed countries cannot utilize their reserves? For example, Australia has considerable remaining gas reserves, with a conservative estimate of CO2-e emissions associated with such reserves sitting at 14,419.07 Mt CO2-e (Geo Science Australia, 2016)

How do we count a country’s carbon budget?

Knowing how to divide the global carbon budget also requires that we accurately measure what a country is currently emitting. The current approach to emissions accounting used by the international community considers emissions produced within territorial borders. This relies on an ethical idea of responsibility for emissions that limits responsibility for those emissions directly caused by a country, what we might call a ‘territorial’ model. But responsibility for emissions accrued in other ways, for example by exporting fossil fuels.

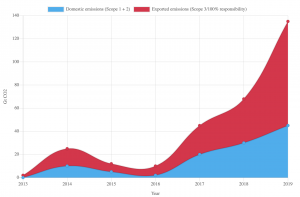

As the following graph illustrates, Australia is a clear net exporter of greenhouse gas emissions. Its national emissions, which are relied upon to work out carbon budget responsibility and emissions reductions targets, are dwarfed by the emissions generated by the burning of fossil fuels that have been mined in Australia and shipped overseas.

Whether we include these exported emissions in a country’s carbon budget or just require that a country pay some of the associated costs, how we make that decision relies on ethical considerations about responsibility.

Why is the carbon budget important?

Using the language of carbon budgets is a useful communicative tool for increasing understanding and motivating action on climate change. Adopting this commonly understood notion of setting a “budget” underlines the planet’s limited capacity to tolerate greenhouse gas emissions and still remain habitable. This allows for the estimation of deadlines and creation of hypothetical scenarios (for example, “If global emissions are reduced by 5% per year, are we still likely to exceed the 2°C limit?”), which heighten the sense of urgency to act on this issue immediately.

Setting a carbon budget also provides a degree of certainty in a field where predictability and accuracy can be hard to come by. This is important for policymakers and other relevant decision-making bodies whose choices ought to be made with awareness of the consequences that certain actions will have on the likelihood of breaching the 2°C limit, and therefore how we should expect and prepare for the effects of dangerous climate change. Finally, carbon budgets enable us to more easily and transparently determine and monitor countries’ emissions reduction targets.

Fundamentally, however, ethical considerations permeate virtually all aspects of the topic of setting carbon budgets. It is undeniable that climate science should inform how carbon budgets are set, but it cannot do so alone. Climate science cannot tell us what level of climate-related harms are acceptable, or how the global carbon budget should be divided between countries. These are ethical questions. Determining what how ambitious a carbon budget should be and how emission rights should be shared requires a clear set of ethical principles.

References

Australian Government. Geoscience Australia. 2016 ‘Gas: Summary’ Retrieved from http://www.ga.gov.au/aera/gas (accessed 16 November 2017).

Caney, S. 2009 ‘Justice and the distribution of greenhouse gas emissions’, Journal of global ethics, vol. 5, no.2, pp.125-46, https://doi.org/10.1080/17449620903110300

Climate Change Authority 2014. Reducing Australia’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions- Targets and Progress Review, Final Report. Australian Government, pp.117-232.

Gosseries, A. 2004. ‘Historical Emissions and Free-Riding’, Ethical Perspectives 11 pp.36-60, p43-46

International Energy Agency. 2012. World Energy Outlook 2012: Executive Summary, <http://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/English.pdf>

IPCC, 2018: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty, Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M.Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)

Jamieson, D 2006. ‘Adaptation, mitigation, and justice’ in Perspectives on Climate Change: Science, Economics, Politics, Ethics.vol. 5, Advances in the Economics of Environmental Resources, vol. 5, pp. 217-248, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1569- 3740(05)05010-8

Knopf, B., Kowarsch, M., Lüken, M., Edenhofer, O. and Luderer, G., 2012. ‘A global carbon market and the allocation of emission rights’ in Climate change, justice and sustainability, pp. 269-285, Springer, Dordrecht. Meyer, Contraction and Convergence: the Global Solution to Climate Change, (Dartington, UK: Green Books, 2000)

Morrow, D. R. 2016. Climate Sins of Our Fathers? Historical Accountability in Distributing Emissions Rights. Ethics, Policy & Environment, Vol. 19, pp. 335-349.

Moss, J. 2016 ‘Mining, morality and the obligations of fossil fuel exporting countries’ Australian Journal of Political Science, Vol.51, no.3, pp.496-511, DOI: 10.1080/10361146.2016.1200533

Moss, J. Kath, R. 2019. ‘Historical Responsibility and the Carbon Budget’, Journal of Applied Philosophy, Vol 36/2, pp. 268-289.

Neumayer, E. 2000. ‘In Defence of Historical Accountability for Greenhouse Gas Emissions’, Ecological Economics. Vol.33, no.2, pp.185-92.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (2016) ‘OECD.Stat, OECD <https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=AIR_GHG>

Page, E. A. 2012. ‘Give It Up for Climate Change: A Defence of the Beneficiary Pays Principle’, International Theory 4: 300-30.

Singer, P. 2002. One World (Melbourne: Text Publishing).

Shue, H. 1999. ‘Global Environment and International Inequality’ International Affairs, vol. 75, no.3, pp.531-45, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.00092

Stocker, T.F. Qin, D. Plattner, G.-K. Tignor, M. Allen, S.K. Boschung, J. Nauels, A. Xia, Y. Bex, V. Midgley, P.M. 2013, ‘Summary for Policymakers’ Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, pp.1-30, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.00